Discussing the triangle spider Hyptiotes paradoxus with a preamble about aerial dispersal.

Some years ago I was employed as a researcher studying dispersal behaviour in spiders. The work focussed on farmland species and in particular linyphiids or money spiders which are thought to deliver important pest controlling benefits for growers. We wanted to monitor dispersal in the field to see how their numbers varied according to species, season, weather, crop type, field operations and so on. The work involved setting up traps in various fields around the farm where the study was taking place.

In dispersing, these small spiders (and juveniles of larger species) release a long length of silk, and use it rather like a kite, to catch the passing air current, allowing the drag on the silk to pull them into the air. This dispersal behaviour is known as ballooning and represents a passive dispersal mechanism where distance and direction are outside the disperser’s control. In contrast to this is active dispersal; for example, when an insect uses its wings to choose where and how far to go. Given the right conditions, a ballooning spider can potentially travel many miles in a single flight. Typically, though, they tend to move over the landscape in a series of shorter hops, sometimes travelling only a few meters at a time. As a rule, height gained equals greater distance travelled, and to give themselves the best chance of a longer flight they usually climb to the top, or suitable prominence, of any structure they happen to land on, whether it be vegetation, fences or even the heads of recumbent cows.

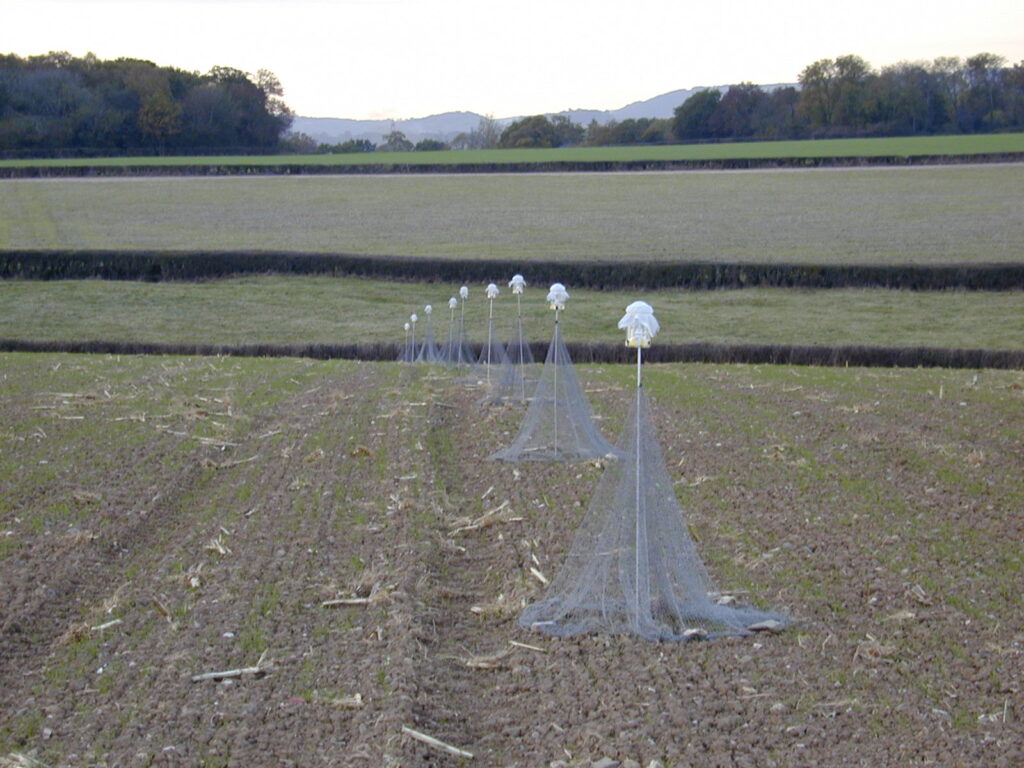

For my first attempt at sampling, I used water traps (large trays filled with a mixture of water and a little detergent to break the surface tension) and unfortunately the results were pretty dismal. The spiders spent more time using the elevated trays as launch pads rather than falling into them, and we caught relatively few. My supervisor and I had a rethink and for our next endeavour we developed a method first used by Eric Duffey (Duffey, 1956) which utilised the dispersing spiders’ desire to climb. The original traps simply consisted of a 2-metre stick or cane with some sticky gum at the top to trap the climbing spiders. In our version, rather than using the likely messy and unpleasant gum, I made a small vessel out of a 2-litre drinks bottle, where the top was cut off and inverted into the bottom to make something similar to a lobster pot which would sit atop the stick. The dispersing spiders would climb the stick and enter the trap through the narrow bottle opening. With some testing, we found that, between daily collections, the majority remained within the trap with only a few escapees. With the addition of a net skirt to better intercept the dispersing spiders, the trap was complete, and it proved very effective, trapping large numbers of live spiders which we could also use in our wind tunnel studies.

The vast majority of spiders collected were typical farmland species e.g. Erigone atra, Oedothorax fuscus and Tenuiphantes tenuis etc., but sometimes I’d come across something quite unusual. On one occasion in late August, I collected a male Hyptiotes paradoxus which stood out straight away from the usual catch with its huge pedipalps and relatively large, almost circular cephalothorax with odd turret-mounted eyes.

This species, also known as the triangle spider, is a member of the Uloboridae, a relatively small family with only two native British species. Uloborids are cribellate spiders, this term relating to the cribellum; a sieve-like plate lying in front of the spinnerets made up of thousands of silk producing spigots. The capture silk made by the cribellum is dry, not gluey, like that of the araneids (orb-weavers), and when combed through specialised bristles on the hind metatarsi or calamistrum, the silk takes on a characteristic fuzzy texture. An unusual feature of these spiders is that they are not venomous, i.e. they have no venom glands, instead relying on their fuzzy silk to immobilise their prey.

This spider also employs another contrivance in capturing prey, from which it takes its name. Its web is triangular in appearance, looking rather like three sections of a normal orb web. At the wide end, the radial threads are connected by strands of capture silk which then taper down to form a single anchor thread at the apex. At this point, the spider forms a living bridge between the mooring point and the web. This web also comes spring-loaded; to prime the web, the spider retreats backwards away from the web, gathering-up slack in the anchor thread as it goes thereby putting the whole web under tension. When an insect flies into the web, the spider immediately lets go of the gathered thread, which releases the tension, allowing the web to collapse around the insect. After a few additional swathes of silk, the prey is immobilised. This process has been documented in the excellent BBC Life in the Undergrowth series; The Silk Spinners (2005).

Hyptiotes paradoxus is a woodland species and given our specimen was found in a very untypical location i.e. in a climbing stick trap set in the middle of a large meadow, it is very likely that the spider was in the process of dispersing. The question was where from? According to the distribution atlas at the time (Harvey et al 2002), the nearest record of H. paradoxus to our location in Devon was quite a distance away, near Budleigh Salterton, some 16 miles to the west.

On the continent, the spider is associated with coniferous woodland and in particular spruce woodland. Whilst there were a number of sitka spruce Picea sitchensis plantations close to us, in the British Isles, occurrences of H. paradoxus are historically known from yew woodland Taxus baccata and where yew, sometimes together box Buxus sempervirens, grow amongst broadleaf trees. Unless our spider had travelled a great distance, the absence of local woodland with a significant yew component made the origin of our specimen quite a mystery. I remember, I did some searching in a couple of the local spruce plantations just in case it might be there, but apart from a lot of opliones and some nice looking Diaea dorsata and eyed ladybirds Anatis ocellata, I drew a blank.

More recent records might shed some light on this situation, where H. paradoxus has been collected from some historically atypical woodland for this species. Indeed, a brief article by Keith Alexander (2020) noted a sub-adult male beaten from old hazels within a mixed woodland comprising oak, ash sycamore and hazel with some holly, this record also from south Devon. Immature spiders were also taken from old heather bushes close by but within a section of wood which was mainly conifer plantation. At another site in Southampton, further subadults were beaten from old hazels again within a woodland comprising oak, hazel and some holly. Alexander emphasised that, although holly was found at two of the locations, the spiders were associated with aerial deadwood networks in the tops of old hazel which formed a subcanopy beneath the broad-leaved trees. These observations, together with historical and recent accounts of H. paradoxus in situations with minimal evergreen understorey, suggest that it’s habitat preference may be wider than previously thought.

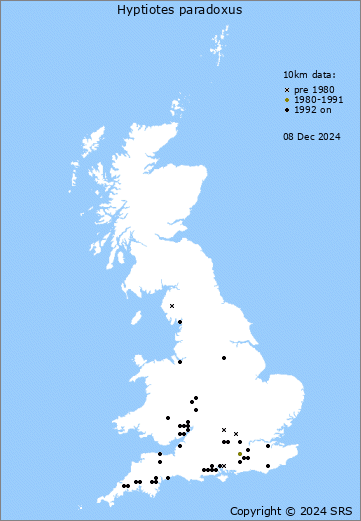

The triangle spider has never been a common spider in the British Isles or indeed over mainland Europe. Many reports appear to be rather sporadic, and there seems to be few places where the spider can be found with some certainty. In the British Isles, the spider occurs in the south and west of England and Wales, with the vast majority of records being found southwest of a line running between the Thames and Mersey Estuaries. Some notable locations include the New Forest, South Hampshire; Box Hill and Wallis Wood, Surrey; Bagley Wood, Oxfordshire; Butler’s Hangings and Hearnton Wood, Buckinghamshire and Grubbins Wood, Westmorland. Recent (1990s) surveys have recorded the spider in the Forest of Dean, Gloucestershire and in the Wye Valley and at Queen’s Wood near Ross, Herefordshire (Askins 1990; Farr-Cox 1990; Merrett in Bratton 1991; Rixom 1998). Merrett (1995, 2000) also gives new county records for Kent, Staffordshire and Dorset.

I was always intrigued by this spider (I didn’t find any more) and a few years later I attended a house-warming party with my wife close to Box Hill in Surrey. Knowing this was a recognised hot spot for this species, we took the opportunity to have look. I didn’t have any equipment with me, and we spent a few hours fruitlessly wandering about sticking our heads into box shrubs and peering amongst the lower branches of the yew trees. The next day we decided to have a quick ‘Hail Mary’ visit and within a few minutes, we found a young yew tree with five spiders in it. The photos above are from this visit. Although you can plainly see the green yew leaves in the photos, the spiders occurred in the lowest part of the tree canopy where the branches were more sparse and a significant portion were dead, possibly being sacrificed owing to pronounced shading at the canopy base.

My experience with this spider is far too limited to ascribe with any certainty what sort of environments H. paradoxus favours. Perhaps these differ on a regional basis and maybe they change developmentally too. Are there functional and structural similarities to the mircohabitats that H. paradoxus has been found inhabiting? Maybe H. paradoxus prefers transitional, edge environments where common factors are difficult to pin down. I would tentatively suggest that areas of low foliar presence might be preferable together with a certain degree of stuctural complexity providing the right support stucture for their triangle webs whilst being within (or adjacent to) an environment open enough for flying insect to pass through. Perhaps a network of dead twigs and branches would constitue suitable conditions? I also wonder whether the unusual web of hyptiotes where the spider plays an active component, places limitations on where their webs can be most effective, certainly for adults. For instance, do they need particularly sheltered locations where disturbance from rain and wind is minimised?

It would be very interesting to find more spiders and see if any of this idle speculation bears out. This year, I took a quick walk through another of their historic haunts, Bagley wood, which isn’t far from where I live. It wasn’t the best time of year so I only had a cursory look around but come August, which is when adult numbers peak, I will be back and hopefully, if I’m lucky enough to find some, I might understand their habits a little better.

Alexander, K. N. A. 2020. Observation of the habitat of Hyptiotes paradoxus at two sites in Devon and Hampshire. Spider Recording Scheme News. No. 96. Newsletter of the British Arachnological Society, 147.

Life in the Undergrowth: The silk spinners (2005) BBC, 6 August [Online]. Available at https://www.dailymotion.com/video/x24gi93 (Accessed 10 November 2024).

Harvey P. R., Nellist D. R., Telfer M. G. 2002. Provisional Atlas of British Spiders. (Arachnida, Araneae). Vol. 1. 1st. Ed. Pub. Biological Records Centre.

Leave a Reply